I was recently asked “why Cinsault?”

My response reflected the competing forces of complexity, planning, and random good luck that goes into wine making.

To explain, let me provide a little general information about the varietal.

Cinsault is considered one of the “minor” grapes form the Southern Rhone region of France. It is generally used for Rosé production, but also often blended into red with Grenache, Syrah, and Mourvèdre, aka the major players, to provide freshness and lift to the wine, as well as floral and fruity aromatics. It has become a more prominent grape in rosé production because it can harvest early, holds onto acidity while still fruity—some have called it an acid candy. In fairness those are the primary characteristics, but there is more to this grape than that.

I like the fresh red raspberry, strawberry, and cherry flavors, peach and a hint of smoke, the light floral, violet, and the touch of spice on the finish. It is light to medium in body with low tannins and medium plus acidity. Like Gamay and Pinot Noir, the grape is fruity, so acid is there, but not so notable on the palate. All of this paired with alcohol levels around 12%, makes this and ideal blending grape for the Rhone style blend that I want to make; or so I thought.

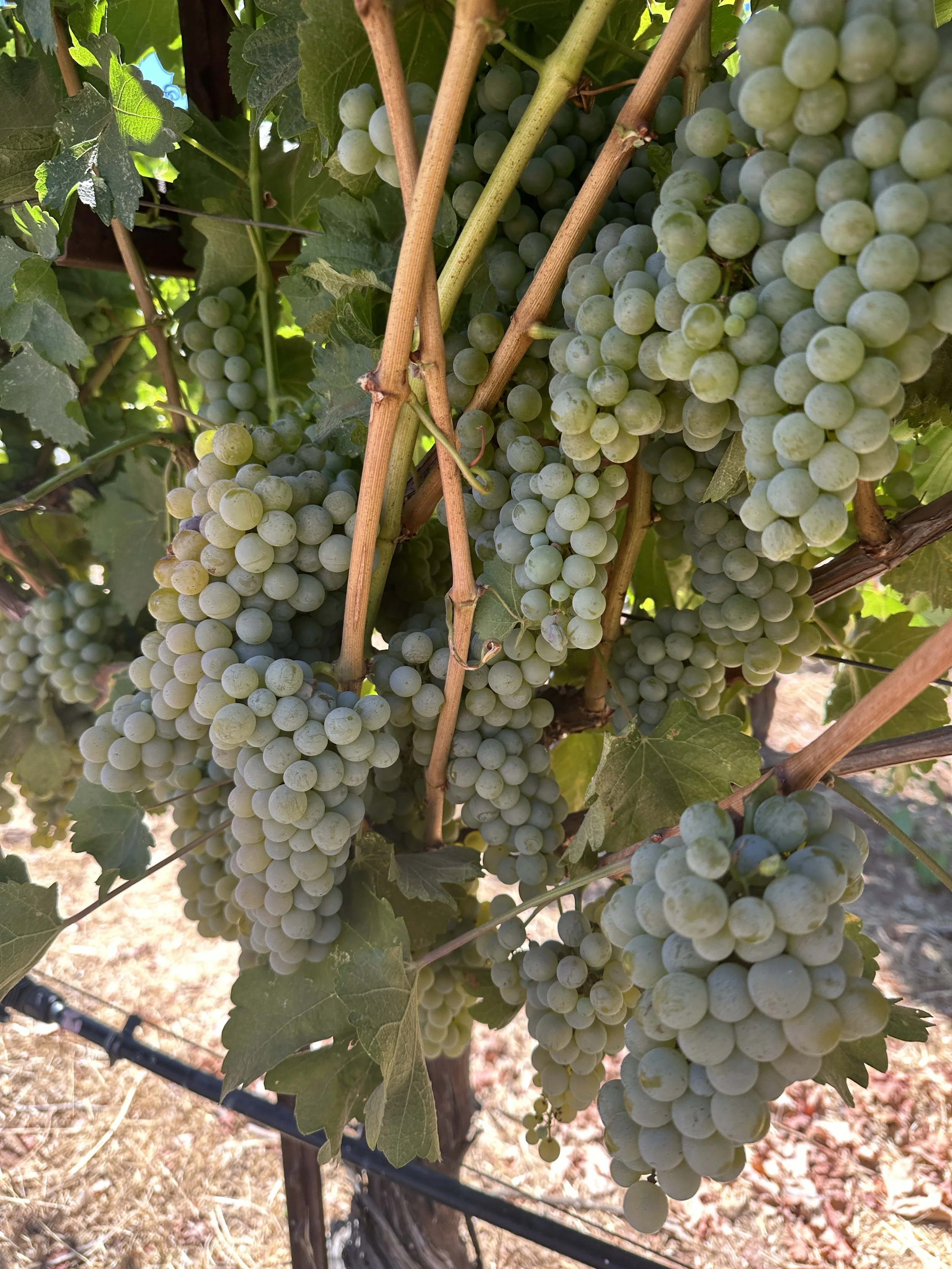

Last year, I got 1 ton of Cinsault from Yolo County, which is about an hour east of St. Helena over the Lake Berryessa pass. The agricultural area out there is arid and hot, but the soil has excellent drainage, and the conditions are good for a grape like Cinsault that is drought resistant, adapts to any soil, and thrives in heat. Steve Metthiasson very gerously turned me on to some Cinsault at JDM Organics, formerly known as Windmill Farm, where Sergio farms meticulously, organically, and is working on biodynamic certification. The grapes are, simply put, beautiful.

I put them on the sorting table just to watch them dance by, pulling out a leaf or two, but otherwise wondering why I added that step at all.

I did a whole cluster, cold fermentation, and the wine came of out fresh, light, and fruity with a balance of acidity that was present and playful without inhibiting the pleasant drinkability of the wine. In January, when I was making decisions about racking and blending, I tasted it, and to my great surprise, the wine tasted great. I could not help imagining that it would be nice by itself, with a chill on a warm summer afternoon. This is a beach wine, I thought! As luck would have it, my friend, Bruce Regalia had some glass to unload. what? Free glass? I can’t turn that down! But, these are red wine bottles, whatever would I bottle now??? Well, you can see how the randomness of winery work, sometimes present us with an opportunity.

I reserved one barrel for the blends that remained in oak for 6 more months, and bottled 40 cases of 100% Cinsault.

There are others that do this grape well. My friends Thenis Kruger at Fram, in South Africa, makes a Cinsault that is also light on its feet and has a wonderful brightness and fruity softness. Also from South Africa, Tremayne Smith makes a 100% Cinsault that ironically has a skull and crossbones on the label, but is the most friendly and unassuming wine. All of these are great chilled, so they meet the “red wine” drinker and the “white wine” drinker at a peaceful center—something we should all be aiming at!

What I love about these wines is the easy approachability that usually is reserved for whites or rosé. They are sippable, cocktail reds. Enjoy them with some light, fresh cheeses and charcuterie while you relax on the beach or while cooking with friends. They are to wine what an amuse bouche is to the meal!

Cheers, Maria